How Computers Understand Meaning

BM25 is fast, reliable, and completely fails when you can’t remember the exact words you’re looking for.

Search for “authentication” and BM25 won’t find documents that say “login.” To BM25, those are different strings. It has no concept that they mean related things.

Vector search fixes this. It finds documents by meaning, not just by words.

Meaning as Coordinates

Here’s the core idea: what if we could place words in space, where similar meanings are close together?

Imagine a map where “dog” and “puppy” are neighbors, “cat” and “kitten” are nearby, and “refrigerator” is off in a distant corner. If you could build such a map, then searching for “puppy” would naturally find documents about “dogs” - they’re in the same neighborhood.

This is what embeddings do. They convert text into coordinates - lists of numbers that represent position in a high-dimensional space. Similar meanings end up with similar coordinates.

The dimensions aren’t things you can name, like “animal-ness” or “size.” They’re abstract features learned from patterns in massive amounts of text. But the result is intuitive: words that appear in similar contexts end up near each other.

“Coffee” and “tea” appear in similar sentences - people drink them in the morning, they’re served hot, they’re caffeinated. So their embeddings are close. “Coffee” and “democracy” rarely share context, so they’re far apart.

How Embeddings Get Made

An embedding model reads text and outputs a vector - a list of, say, 768 numbers. Those numbers are the coordinates.

The model learns these representations during training. It sees billions of sentences and learns to predict words from context. In the process, it develops internal representations where similar things cluster together.

You don’t train these models yourself. You use pre-trained ones. Modern embedding models like Gemma or E5 are small enough to run locally - a few hundred megabytes. Feed them a sentence, get back coordinates.

The key insight: if you embed both your documents and your search query using the same model, you can find documents by asking “which document coordinates are closest to my query coordinates?”

Cosine Similarity: Which Way Are You Pointing?

Once you have coordinates, you need a way to measure closeness. The standard approach is cosine similarity.

Think of each vector as an arrow pointing from the origin to its coordinates. Cosine similarity measures the angle between two arrows. If they point in the same direction, similarity is 1. If they’re perpendicular, it’s 0. If they point opposite ways, it’s -1.

Why angles instead of distances? Because it handles magnitude differences gracefully. A long document and a short document about the same topic will have vectors pointing the same direction, even if one vector is “longer” (has larger coordinate values). The direction captures meaning; the length is mostly noise.

When you search “how users prove their identity,” vector search:

- Embeds your query into a vector

- Compares that vector against all stored document vectors

- Returns documents with the highest cosine similarity

Documents about authentication, login, credentials, and identity verification all end up near each other in the embedding space. Your query about “proving identity” lands in the same neighborhood, so they match - even though the words are different.

The Problem With Big Documents

There’s a catch. Embedding models have context windows - limits on how much text they can process at once. A typical embedding model might handle 512 or 2048 tokens (roughly words).

Your documents are often longer. A meeting transcript might be 10,000 words. A technical spec might be 5,000. You can’t just feed the whole thing into the embedding model.

But what if you could? Would you even want to? A single embedding for a 10,000-word document would be a blurry average of everything in it. Search for “authentication” and you’d match a document that mentions authentication once in a sea of unrelated content - because the embedding represents the whole document, not the relevant part.

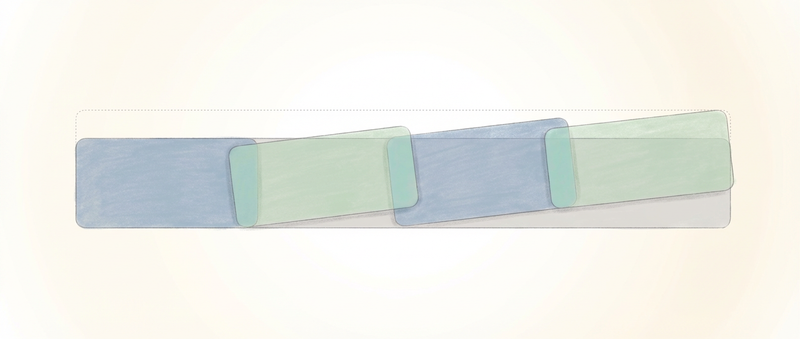

The solution is chunking: splitting documents into smaller pieces, each with its own embedding.

Chunking: The Art of Slicing Text

A common approach chunks documents into pieces of about 800 tokens each. That’s roughly 600 words, or about a page of text.

Why 800? It’s a tradeoff:

- Too small (100 tokens): You lose context. A chunk about “it” doesn’t tell you what “it” refers to.

- Too large (4000 tokens): You’re back to blurry averages. Specific topics get diluted.

- 800 tokens: Big enough to contain a coherent idea, small enough to be specific.

But there’s a problem with slicing text: you might cut right through an important passage. If a paragraph about authentication gets split between two chunks, neither chunk has the complete picture.

The fix is overlap. Each chunk shares some content (typically 10-20%) with the next chunk. The end of chunk 1 overlaps with the beginning of chunk 2.

This means text near chunk boundaries appears in two chunks. If your search matches that text, you’ll find it - it won’t fall through the cracks.

More overlap means better boundary coverage but more storage and slower indexing. Less overlap means faster indexing but more risk of missing boundary content. 15% is a reasonable middle ground.

What Gets Stored

When you index documents for vector search:

- Each document gets split into chunks with overlap

- Each chunk gets embedded into a vector (768 or so numbers)

- Vectors get stored in an index alongside the original text

A 5,000-word document might become 8-10 chunks, each with its own embedding. When you search, the system checks all chunks and returns the ones whose vectors are closest to your query.

The results show which chunk matched, not just which document. This is useful - you see the specific passage that’s relevant, not just “somewhere in this giant file.”

Where Vector Search Shines

Vector search excels at conceptual queries:

- “How users prove their identity” finds authentication docs even if they say “login”

- “Making containers talk to each other” finds networking docs regardless of terminology

- “Why is the build failing” matches troubleshooting guides phrased differently

It’s also robust to phrasing. “User authentication flow,” “how login works,” and “verifying user identity” all land in similar regions of embedding space. Vector search finds the same documents regardless of how you phrase the question.

Where Vector Search Struggles

Vector search isn’t perfect. It has blind spots that BM25 handles better:

Exact terms: Search for “ECONNREFUSED” and vector search might return documents about network errors in general. BM25 would find the exact error message.

Rare technical terms: Embedding models are trained on common text. Obscure jargon, internal code names, or domain-specific terminology might not be well-represented in the embedding space.

Precision vs recall: Vector search casts a wide net. Sometimes you want exactly what you typed, not semantically related content.

This is why the best search systems offer both approaches. BM25 when you know the exact terms. Vectors when you’re exploring concepts. And increasingly, hybrids that combine both signals.

The Local Advantage

I’ve written before about the advantages of local models. For search, the benefits are clear:

- Privacy: Your documents never touch external servers

- Speed: No network latency, no rate limits

- Cost: After setup, every query is free

- Reliability: Works offline, no service dependencies

Modern embedding models are small enough to run on modest hardware. They download once and cache locally. The tradeoff is that they’re less powerful than massive cloud models - but for document search, they’re more than sufficient.

The Takeaway

Embeddings convert meaning into coordinates. Similar meanings cluster together. Cosine similarity measures how close two meanings are.

Chunking handles long documents by splitting them into pieces small enough to embed meaningfully, with overlap to avoid losing content at boundaries.

Together, these techniques let you search by concept rather than by keyword. “Authentication,” “login,” and “proving identity” all find the same documents - because they mean the same thing, even though the words are different.

BM25 asks: “Does this document contain these words?”

Vector search asks: “Is this document about the same thing as my query?”

Both questions are useful. The best search systems answer both.