How Computers Find Words

Every search engine you’ve ever used runs on an algorithm from 1994. Google, DuckDuckGo, the search bar in your email client - underneath all the machine learning, there’s a formula called BM25 doing the heavy lifting.

BM25 is where search starts. Understanding it explains why some queries work beautifully and others return garbage.

The Grep Problem

Let’s start with the simplest possible search: grep. You have files, you want to find which ones contain a word. Grep scans through them and returns matches.

This works when you remember exactly what you’re looking for. If I know I wrote “ECONNREFUSED” in some error handling code, grep finds it instantly.

But most searches aren’t like that. I vaguely remember a conversation about authentication. Did I call it “auth”? “Authentication”? “Login flow”? “Identity verification”? Grep needs me to guess right. If I guess wrong, I get nothing.

Even when grep finds matches, they’re unsorted. A file that mentions “authentication” once in passing ranks the same as a file entirely about authentication. That’s not helpful when you have hundreds of matches.

BM25 solves the ranking problem. It scores results by relevance using surprisingly simple intuitions about what makes a document match a query well.

Rare Words Matter More

Imagine searching for “authentication error handling” across your notes.

The word “the” probably appears in every document. Finding “the” tells you nothing - it doesn’t help distinguish relevant documents from irrelevant ones.

The word “authentication” appears in maybe 5% of your documents. Finding it is meaningful - this document is probably about authentication.

The word “ECONNREFUSED” appears in maybe 0.1% of your documents. Finding it is very meaningful - this document almost certainly discusses that specific error.

BM25 formalizes this intuition. It weights rare terms higher and common terms lower. The technical name is “inverse document frequency” - the less frequently a term appears across all documents, the more it matters when it does appear.

This is why search engines handle stopwords (the, a, an, is, are) gracefully. They’re not removed or ignored - they just contribute almost nothing to the ranking because they appear everywhere.

Repetition Has Limits

If a document mentions “authentication” once, that’s a signal. If it mentions “authentication” fifty times, that’s a stronger signal. But is it fifty times stronger?

You might think so, but no. A document that says “authentication” fifty times isn’t necessarily more relevant than one that says it ten times. At some point, you’re just being repetitive.

BM25 handles this with “term frequency saturation.” The first few occurrences of a word boost relevance significantly. Additional occurrences help less and less. Eventually, more repetition barely moves the needle.

This prevents keyword stuffing from gaming the rankings. A document that artificially repeats search terms won’t dominate just because it has high raw counts.

Document Length Matters

Consider two documents:

- Document A: 200 words, mentions “authentication” 5 times

- Document B: 10,000 words, mentions “authentication” 5 times

Which is more relevant to a search for “authentication”?

Probably Document A. It’s short and 2.5% of it is about authentication. Document B is long and authentication is just 0.05% of the content - probably a passing mention in a larger piece.

BM25 normalizes for document length. A match in a short document counts for more than the same match in a long document. This prevents lengthy documents from dominating results just because they contain more words.

The Formula You Don’t Need to Memorize

BM25 combines these three intuitions into a single relevance score:

- Rare terms get more weight (inverse document frequency)

- Repetition helps, but with diminishing returns (saturating term frequency)

- Matches in shorter documents count more (length normalization)

The actual formula has tunable constants, but the intuitions are what matter. BM25 asks: “How much does finding these specific words in this specific document tell me about relevance?”

A document mentioning rare search terms multiple times without being padded with filler content scores well. A document barely touching on common words in a sea of unrelated text scores poorly.

Why This Still Matters

BM25 was published in 1994. In tech years, that’s ancient. Why is it still foundational?

Because it’s fast and it works.

BM25 doesn’t require machine learning. It doesn’t need GPUs or training data. You can implement it with basic data structures and run it on any hardware. SQLite’s FTS5 (Full-Text Search 5) extension implements BM25, which means any application with SQLite gets competent search almost for free.

For precise searches - error messages, function names, specific technical terms - BM25 is hard to beat. It does exactly what you want: finding documents that contain the words you typed, ranked by how relevant those matches seem.

Where BM25 Falls Short

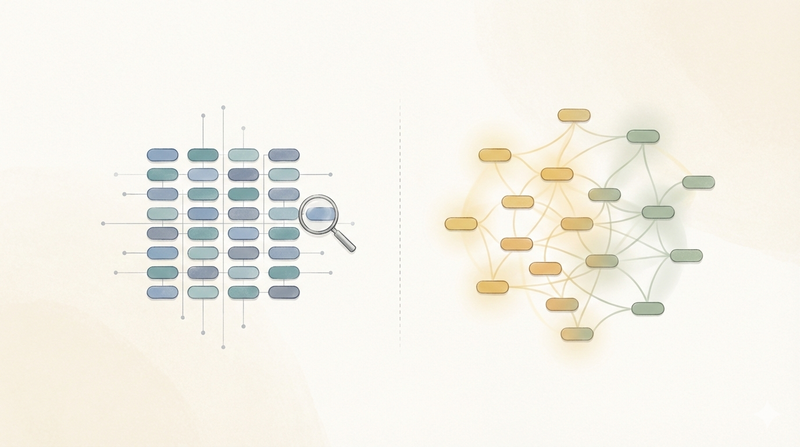

BM25 has a fundamental limitation: it only understands words, not meaning.

If you search for “authentication,” BM25 will not find documents that only use the word “login.” To BM25, those are completely different strings. It has no concept of synonyms, related concepts, or semantic similarity.

BM25 fails when:

- You don’t remember the exact terminology (“auth” vs “authentication”)

- The document uses different words for the same concept (“credentials” vs “password”)

- You’re searching for a concept rather than specific words (“how users prove their identity”)

BM25 also can’t handle typos. Search for “authentcation” (missing an ‘i’) and you’ll get nothing, even if you have dozens of relevant documents.

These limitations are fundamental to how BM25 works. It compares character sequences, not meaning. For thirty years, this was an acceptable tradeoff - the speed and simplicity were worth the occasional missed result.

Now there are other options. Vector search understands meaning rather than just words. The old algorithm isn’t obsolete; it’s just no longer alone.

The Takeaway

BM25 embodies a few simple truths about text search:

- Rare words are more informative than common words

- Repetition matters, but not linearly

- Shorter documents with matches are probably more focused

These intuitions are timeless. They applied in 1994 and they apply today. Understanding BM25 helps you understand why search behaves the way it does - why some queries return great results and others miss obvious matches.

When a query fails, it’s usually because you’re asking for meaning and BM25 only knows words. That’s not a flaw in the algorithm - it’s a limitation of the approach. One that newer techniques address, but never fully replace. Sometimes you really do want exact word matching, and a thirty-year-old formula will be there when you do.