The Closing Gates of Open Source

I tried to contribute a fix to beads_viewer recently. Found a real bug where a hardcoded path should have used a stored variable, wrote up a clean fix, and submitted the PR. The maintainer acknowledged the bug was legitimate, thanked me for finding it, and then hit me with something I’d never heard before: “we don’t accept outside code contributions for this project.”

I was shocked. This wasn’t a rejection because my code was bad or my approach was wrong. The door was simply closed to everyone. The maintainer offered to re-implement the fix themselves, which felt strange - they’d essentially take my idea and write it again from scratch. I asked them to at least document the policy in the README so other people don’t waste their time discovering this the hard way.

That experience stuck with me, and then I started seeing the pattern everywhere.

The Pattern

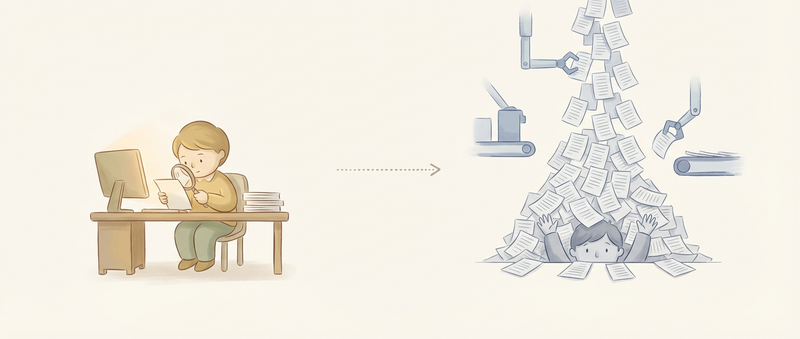

Days later I saw tweets about major GitHub repositories stopping external contributions. The reason: unprecedented levels of AI-generated slop flooding their pull request queues.

tldraw announced they would automatically close pull requests from external contributors going forward:

“Like many other open-source projects on GitHub, we’ve recently seen a significant increase in contributions generated entirely by AI tools.”

The submissions suffer from incomplete context and fundamental misunderstandings of how the codebase works. Worse, the people submitting them rarely stick around for the back-and-forth that any real contribution requires. An open pull request represents a commitment from maintainers to review it seriously, to engage with the contributor, to shepherd the change through to completion. When the signal-to-noise ratio collapses, that commitment becomes impossible to sustain.

I get why maintainers are doing this. Open source maintenance is exhausting even under the best circumstances. Every PR needs careful review, testing, communication, and often multiple rounds of revision. When most of what lands in your queue is low-quality AI slop from people who won’t be there for the follow-up, the cost-benefit math completely breaks down. But something valuable is being lost in the process.

The Ladder We Climbed

Open source contributions gave me a lot of exposure early in my career. It’s how I got my name out there, learned how real projects work, and connected with people who were better than me.

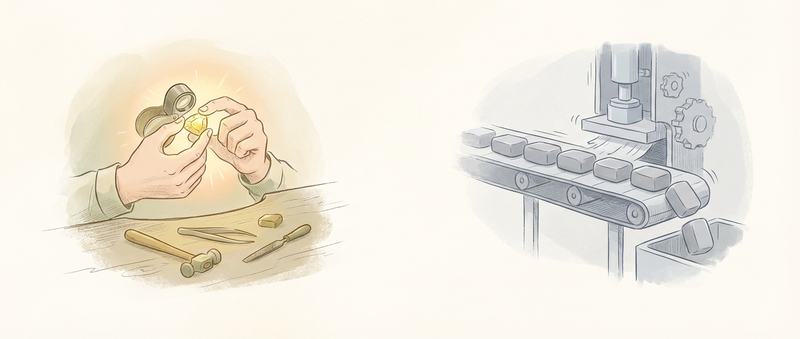

The process was straightforward but powerful. You find a project you actually use. You hit a bug that annoys you. You dig into the codebase, figure out what’s going wrong, and fix it. You submit a PR. The maintainer reviews it, maybe asks for changes, and you go back and forth until the code is ready. Through that process you learn how real codebases are structured, how to communicate with other developers asynchronously, how to write code that works with existing patterns rather than against them.

That door is closing now, and I worry about what happens to the next generation of developers.

When I mentored junior engineers, my advice was always the same: contribute to open source. Pick projects you genuinely care about and fix problems that annoy you. The learning that happens through that process is something no tutorial or bootcamp can replicate. You develop an intuition for how software systems work at scale, how to navigate unfamiliar code, how to communicate technical ideas clearly to people you’ve never met.

If that path is no longer available, we’re making things significantly harder for people trying to enter this field. The ladder we climbed is being pulled up behind us.

The Vibe Coding Problem

Even so, part of me understands why this is happening.

The tools make it dangerously easy. You can point Claude at a repository, describe a bug vaguely, and get a pull request in minutes. You don’t need to understand the codebase architecture. You don’t need to diagnose the root cause of the problem. You just paste the output and click submit. The friction that used to filter for genuine engagement has been almost entirely removed.

I’ve written before about vibe coding and what it means when code becomes disposable. Steve Yegge built Beads - 225,000 lines of Go - without ever looking at the code himself. It shipped, it delivered real value to real people, but the technical debt ran deep. That approach works when you own the whole thing and can iterate freely. It falls apart when you’re contributing to someone else’s project.

The same dynamic is now playing out across open source. People submit PRs they don’t understand, to fix problems they haven’t actually diagnosed, using code they couldn’t maintain if their lives depended on it. Sometimes the PR even works on the surface. But when it doesn’t - when it breaks something subtle, when it needs iteration, when the maintainer asks a clarifying question - there’s nobody home. The person who submitted it has already moved on to their next AI-assisted drive-by.

You can’t check your brain at the door when contributing to open source. If you don’t understand what you’re submitting, you’re not helping - you’re just shifting the burden onto maintainers who now have to figure out whether your contribution is sound, often with zero assistance from you. That’s not collaboration. That’s dumping work on volunteers.

There’s an irony here. Claude Code itself is reportedly 100% vibe coded - built entirely through AI-assisted development. And it works, it’s actually a good product. The approach seems to be: iterate until it works, worry less about the intermediate steps.

I’ve been wrestling with this tension myself. In my beads post I admitted I was trying to let go of caring so much about code quality - treating code as disposable rather than precious. But I keep coming back to the same conclusion: I’m not ready to completely stop caring about what’s being generated. The leverage comes from collaboration with the AI, not from blind delegation. When you submit something to an open source project, you’re asking maintainers to trust your judgment. If you’ve outsourced that judgment entirely to an AI you didn’t supervise, you’re wasting everyone’s time.

The Fun Part

I’m having more fun coding now than I have in years.

AI has unlocked experimentation in ways that weren’t practical before. Complex algorithms and data structures that would have taken weeks to implement correctly can now be explored in an afternoon. I recently wanted to understand CRDTs and Lamport clocks better, so I started building Sterna, my own experiment at a beads replacement. The idea might be overkill, might even be stupid, but it was genuinely fun to build and the thing actually works.

I think that’s what antirez is getting at. The creator of Redis recently wrote about his own experience with AI-assisted development. In a single week of prompting and inspecting code, he modified his linenoise library to support UTF-8, fixed transient Redis test failures, created a pure C library for BERT inference in 700 lines, and reproduced weeks of Redis Streams work in about 20 minutes.

“It is now clear that for most projects, writing the code yourself is no longer sensible, if not to have fun.”

And on the passion for building:

“What was the fire inside you, when you coded till night to see your project working? It was building. And now you can build more and better, if you find your way to use AI effectively. The fun is still there, untouched.”

I’m more bullish than antirez on this. The productivity gains are real and I use these tools constantly. I’ve written about staying in the “smart zone” and managing context effectively. When you know what you’re doing, the gains are insane.

But I diverge from antirez on one point: I still care about understanding the output. He says “writing code is no longer needed for the most part.” I’d frame it differently - writing code is changing, not disappearing. The leverage comes from collaboration, not from turning your brain off and letting the AI drive.

The Taste Problem

I’m not claiming my taste in code is better than anyone else’s. But I do have opinions - about how code should look, how systems should be structured, when a solution is elegant versus when it’s a hack waiting to bite you. Those opinions came from 20+ years of writing code the hard way, making mistakes, and learning what actually works in production.

That experience is what lets me evaluate AI output meaningfully. How do you develop that taste if you never write code yourself? If you never struggle through a problem manually? If you never have a PR rejected and have to figure out why?

Taste requires exposure and iteration. You develop heuristics through experience - writing bad code, having it rejected, learning what actually works in production versus what just looks plausible. If junior developers can’t get their PRs accepted anywhere, if they’re just prompting AI and submitting the output without understanding it, where’s the feedback loop that builds judgment?

No Answers

I don’t have solutions. I’m concerned and working through it myself.

Open source contribution used to be a door into this industry. It was how you proved yourself when you had no professional experience. It was how you learned from people better than you by actually engaging with their code and their feedback. It was how communities formed around shared problems and collective ownership.

That model assumed contributors understood their contributions. It assumed maintainers could trust that someone would be there to iterate when issues came up. It assumed the cost of review was worth the benefit of community input. AI broke those assumptions - not because AI is bad, but because it removed the friction that used to filter for genuine engagement. When contributing is as easy as “prompt and submit,” you get a flood of contributions from people who aren’t really there.

The maintainers closing their gates are responding rationally. They’re protecting their time and their projects and their sanity. I don’t blame them at all.

But we need to think about what we’re losing. Maybe the answer is new contribution models with more structured onboarding, proof-of-understanding requirements, or tiered access based on track record. Maybe the answer is accepting that open source contribution as we knew it was a historical anomaly, enabled by specific conditions that no longer exist. Or maybe we need entirely new ways for people to build taste and prove competence before they contribute - ways that work in a world where AI can generate plausible-looking code on demand.

I don’t know. I’m still working it out. But watching those gates close feels like watching something important slip away. As antirez puts it: “Skipping AI is not going to help you or your career… Test these new tools, with care, with weeks of work, not in a five minutes test where you can just reinforce your own beliefs.” The fire he talks about - the passion for building - that’s still there. The question is how we pass it to the next generation when the paths we took are being walled off.